STEFANO MARIA BARATTI

by

![]()

The iconology of ritual gestures in Christian art over the centuries that connote phenomena of mysticism within the dimension of sacred contemplation, offers a series of processes that are ascribed to the consequence of dramatic conventions, such as a sense of deep emotion – usually evoked in its ancient Greek meaning of «συμπάθεια» (“suffering together”) – or in a state of “trance”, through theatrical gestures that manifest the inception of a theophany.

Since the Catholic Counter Reformation, all visual-gestural language associated with transcendental themes manifests itself in colorful ways by virtue of ecstasies and visions, involving direct experiences “beyond” any logical-discursive thought and according to the inner strength of the subject: within the context of baroque make believe, there are figures that remain unconscious, others that levitate or end up transfixed while standing or kneeling, eyes that roll backwards (as in the “vision within a vision” during the “flights” of Saint Joseph of Copertino), and there are also representations of bodies caught in sensual ecstasy (as in the case of Franciscan Tertiary Ludovica Albertoni, a sculpture by by Gian Lorenzo Bernini), which, in Freudian terms, indirectly recalls a sexual climax – a mystical rapture that combines high spirituality with heightened sexual tension. The body language of prayer seems to involve both the physical part (the five senses) as well as the immaterial and transcendent part (the soul) and represents, as it were, a kind of “receptor” for the divine in the synthesis of rational and irrational forms, thus triggering psycho-physiological reactions between the sacred and the profane.

- Regarding the “emotional” approach of the viewer, it should be noted that the spread of multiple layers of meaning in the works of art depicting ritual gestures through the convention of religious ecstasy (especially in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, thanks to the sketches of Charles Le Brun and his physiognomy charts) opens the floodgates to countless fields of investigation exploring the unconscious: from simple prostrations and genuflections, to ecstatic glances and pathetic gestures, from the blessing hand during the liturgy (“Dextera Domini”) to the mystical “flights” and finally to the stigmata, the physical signs of the Passion of Christ, iconographic attributes of Saint Francis of Assisi and Saint Catherine of Siena.

Through the centuries, the variegated range of works that make up the main body of visual dialogue in regard to transcendental themes, has been classified according to the various artistic currents and aesthetic needs that to this date continue to question the various relationships between art and religiosity.

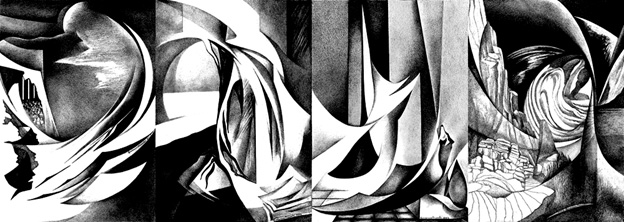

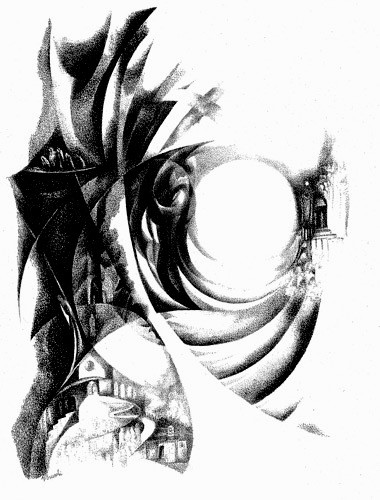

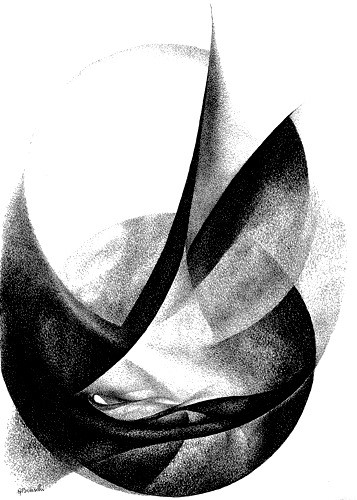

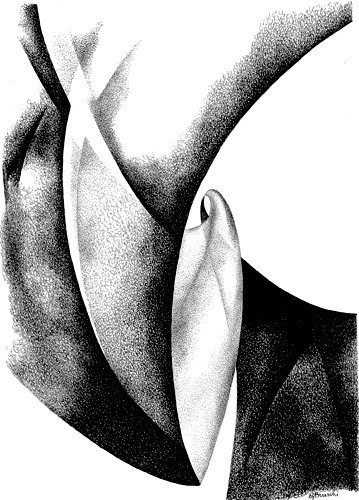

In this perspective, the contribution proposed in the series of engravings entitled Mystical experience of Saint Angela of Foligno by the Perugian artist Giovanna Bruschi – one of the most singular voices in the Umbrian art scene in the last decades – draws its expressive richness from heterogeneous mystical experiences that outline the artist’s original and constantly evolving creative path.

After a period of intense experimentation in the Seventies, Giovanna Bruschi turns to etching as her favorite medium, a technique that allows for an indirect engraving on a matrix with the use of corrosive substances that bite the metal and trace furrows on selected slabs. The dominant traits of Bruschi’s art are now clearly visible, as well as the growth in the various phases of her visual language, inherited from the lessons of her teachers, especially from the futurist Gerardo Dottori, whose aeropainting (aerial bird’s eye views of landscapes) she initially introduces as a leit -motif in her etchings. This gives rise to rhythmic compositions equipped with a visual grammar (shapes, lines, shades) that repeats decorative elements, increasing and decreasing concentric or radial rhythms in a circular compositions, suggesting a «thirst for the beyond» as Bruschi points out in her biography.

Beyond the stylistic influence of futurism, the artist becomes a sensitive interpreter of the profound changes in the evolutionary path of her Christian conscience. Bruschi moves away from any figurative patheticism and refuses all melancholic sentimentality in order to highlight an abstract interpretation of the soul searching for the truth, thus presenting the viewer with a series of clues: oblique and asymmetrical compositions as painful reminders of a descent in the inaccessible depths of our own existence, mimicking the required steps followed by Christian saints through the “dark night of the soul”, a period of intense sadness, fear, anguish , confusion and loneliness, all necessary stages to get closer to God. This concept – the mystic’s journey in to the dark adversities encountered after the divorce from the sensible world – as outlined by the Spanish presbyter and poet Giovanni della Croce (Yepes Álvarez, 1542 – 1591), is present in Christian mysticism Christian since the time of the Fathers of the Church.

In the mystical experiences of the Franciscan Tertiary, Angela of Foligno (1248-1309) – recently canonized by Pope Francis in 2013 – Bruschi retraces the stages of the spiritual autobiography of the saint, interpreting with her engravings the sensations of the “thirty steps” that the soul of Angela accomplishes, following the example of Saint Francis of Assisi, reaching intimate communion with God, through meditation on the mysteries of Christ, on the Eucharist, and on temptations and penances.

The Umbrian artist’s etchings, touching the apex of her technical virtuosity, adopt a restless and fluid graphic style, which involves the actual white of the paper. Bruschi engraves on the varnish, with features comparable to those of a pen, the tension of a chiaroscuro determined by pointed and elongated shapes, often repeating the sequence of images traced with particular types of blur, in a dynamism organized by lines of force that capture and transport the viewer into a vortex dominated by a sense of religious silence.

In these spaces one can detect the “pain of the soul” as a manifestation of psychopathology and mysticism, the same inner chaos described by the mystics of all time, from the visions of Saint Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), to the experiences of Teresa of Avila (1515-1582 ), as well as the merging of dense matter into a process of self-conscious thought. In this series of engravings, the perception of movement is not limited to a recurrent visual motif, but is imposed as an organization principle that underlies Bruschi’s creative drive. The artist seems to interpret the language of an oracle, almost a code of occult mathematics, or an “internal knowledge”, close to the forces and ambivalent forms of nature, in which the soul as “viriditas” forms the essential duality of things.

In a world dominated by the hedonism and the hegemony of a Homo destitutus – who has lost a reference to God in favor of a reality full of anguish – Giovanna Bruschi’s engravings advance a theory of clear geometric patterns and stroboscopic sequences allowing us to capture the sensations inspired by a dramatic ending: the effect of a light that shines at the end of the dark night of the soul.

Stefano Maria Baratti

[Giovanna Bruschi graduates from the “Istituto d’Arte Bernardino di Betto” in Perugia, her hometown; she quickly obtains a License in Painting at the “Academy of Fine Arts Pietro Vannucci”, annexed to the same institute, experiencing the cultural-educational environment of her renown teachers such as Gerardo Dottori, Diego Donati, Adelmo Maribelli and Dante Filippucci. Subsequently she earns a qualification for the teaching of Drawing and History of Art starting to teach in various high schools and at the experimental institute “I.T.A.S. Giordano Bruno” in Perugia, where in addition to teaching History of Art, she coordinates various groups of teachers and students involved in art projects and activities. She frequents the studio of the famous engraver Diego Donati, whom she considers to be her mentor.

Bruschi’s output is fertile and highly productive, especially in the mystical-theological genre, and her works Angela da Foligno: True Poverty (2001) and Rita da Cascia: Between History and Tradition (2002) are soon published by Edimond, Città di Castello, while her most significant works appear in public exhibitions, private galleries and museum collections. Present in cultural circles and academies, she received the award of Academic of Merit from the “Academy of Fine Arts Pietro Vannucci”; she is an Ordinary Member of the “Properziana Academy of Subasio” in Assisi; in May 2007 she received the “Culture Award” The Corimbo “Thought and Images”(6th Edition) and she is registered as a Honorary Member of the Gold Award. Since 1985 she has been working in the Archive for the Italian Art of the Twentieth Century at the Kunsthistorisches Institut of Florence and since 2005, in the Bioiconographic Archive of the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome. Among her recent achievements are a series of prizes won during a number of competitions, as well as personal and collective exhibitions that were well received at a national level.]